Crying over spilt milk: Are the marketing practices to promote infant baby formula jeopardising breastfeeding?

The role of a mother in the development of an infant is invaluable. Whether it be supporting intellectual development or social development at an early age, there remains and even more crucial form of development. Nutritional development. To mark the significance of nutritional development in the early weeks and months of a babies’ life, the first week of August (1st-7th) is considered World Breastfeeding Week by the World Alliance for Breastfeeding Action (WABA). WABA is a global network of individuals and organisations dedicated to the protection, promotion and support of breastfeeding worldwide. However, it would seem that the message and rationale promulgated by WABA faces much challenge whilst heading towards a collision course with the proprietors of instant baby formula milk (IBFM) a form of breast milk substitute (BMS) and their proliferation over the previous decades.

This article will explore how and whether the marketing practices deployed to promote BMS affects and hence jeopardises breastfeeding. We shall look at the importance and significance of breastfeeding, the current challenges and barriers to breastfeeding. We’ll review the marketing practices used by brand labels of IBFM and rebuttals they propose to these claims. Finally, we shall conclude on the repercussions of these claims on the marketing practices and their impact on breastfeeding and IBFM, before providing a conclusion.

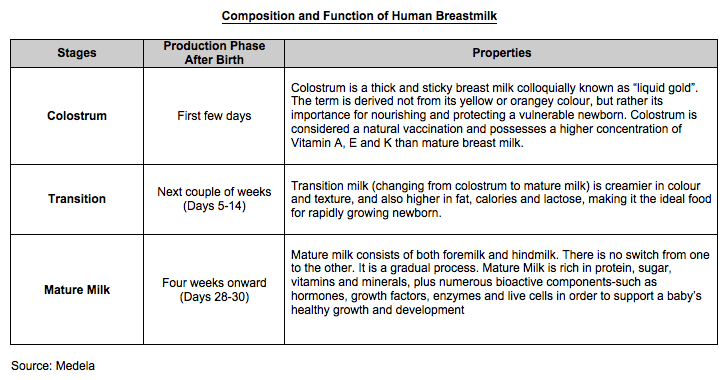

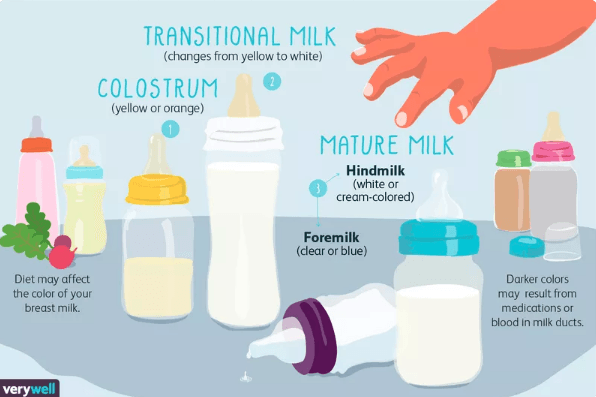

Breastfeeding is one of the earliest and vital acts a mother engages in to support the physiological and nutritional development of her baby. It is for this reason why the World Health Organisation (WHO) recommends solely breastfeeding babies for the first six months of their life. 1 The WHO’s recommendation stems from the constituents of human breast milk, all of which contain basic essential nutrients such as carbohydrates, protein and fats too. Apart from breast milk being tailor made for a mother’s baby, breast milk is rich in million of live cells (white blood cells and stem cells etc.) that are immune-boosting and help organs develop and heal. Breast milk contains enzymes, growth factors, antibodies known as immunoglobulins (key in protecting the baby from illness and infections) by neutralising bacteria and viruses. In addition to this breast milk includes long-chain fatty acids, which play a pivotal part in the development of a babies nervous system, brain and eye development. Finally, breast milk contains 1,400 microRNAs which are thought to regulate gene expression crucial in preventing or halting disease development, whilst supporting the babies immune system and remodeling of the mother’s breast. 2 The development and properties of breast milk occur over three stages; colostrum, transitional milk and mature milk (foremilk & hindmilk).

Source: Very Well

There are numerous research studies attesting to benefits of breastfeeding considering that cognitive development was improved by breastfeeding and as such, breastfed babies performed better on intelligence tests. 3 Though these findings have been challenged, as it remains unclear whether there is a direct relationship or whether other characteristics are associated. 4 Irrespective of establishing a correlation, breastfed babies had lower rates of obesity, diabetes (both type 1 & 2), hypertension, cardiovascular disease, hyperlipidemia and some types of cancer. 5 Though the benefits of breastfeeding seem numerous and a conclusive option, there remains challenges and barriers to breastfeeding.

For some mothers, the act of breastfeeding is not possible and as such it proves to be a challenge in meeting the nutritional needs of the baby. According to the latest data collated by the NHS, the UK had one of the lowest breastfeeding rates at last count in 2010 with 55% of women breastfeeding at six weeks and just 34% doing so at six months. 6 From the latest data, 2016-17, despite a slight increase in the two previous years (2014-15 and 2015-16) breastfeeding prevalence at six to eight weeks afterbirth is 44.4%, a considerably lower rate in comparison to nations like Norway, which achieves rates of 71% at six to eight weeks. 7 Furthermore, only 1 in 200, 0.5%, UK women do any breastfeeding after a year in comparison to Germany with 23%, USA with 27% and Brazil with 56%. 8 Despite, the above findings, 90% of mothers who stop breastfeeding in the early days do so before they wanted to. 9 About 80% of new mothers in England attempt to breastfeed after giving birth, with only 1% of babies being exclusively breastfed until they are six months old, contrary to the recommendations made by the NHS. 10 Common reasons for prematurely stopping breastfeeding given by mothers, include pain and lack of support as reported in a 2016 survey by 60% of 300 mothers surveyed. 11 Difficulties and challenges in breastfeeding can prove a sensitive topic not to mention a period of greater vulnerability to mothers, especially first time mothers. Social pressures can further compound this feeling and amplifies myths speaking, erroneously, to the quality of the mother and relationship (maternal bonding) she has with her baby. Such angst over this period in motherhood is detrimental psychologically to the mother and nutritionally to the baby. Remedies to these situations arise from the use of BMS, especially IBFM.

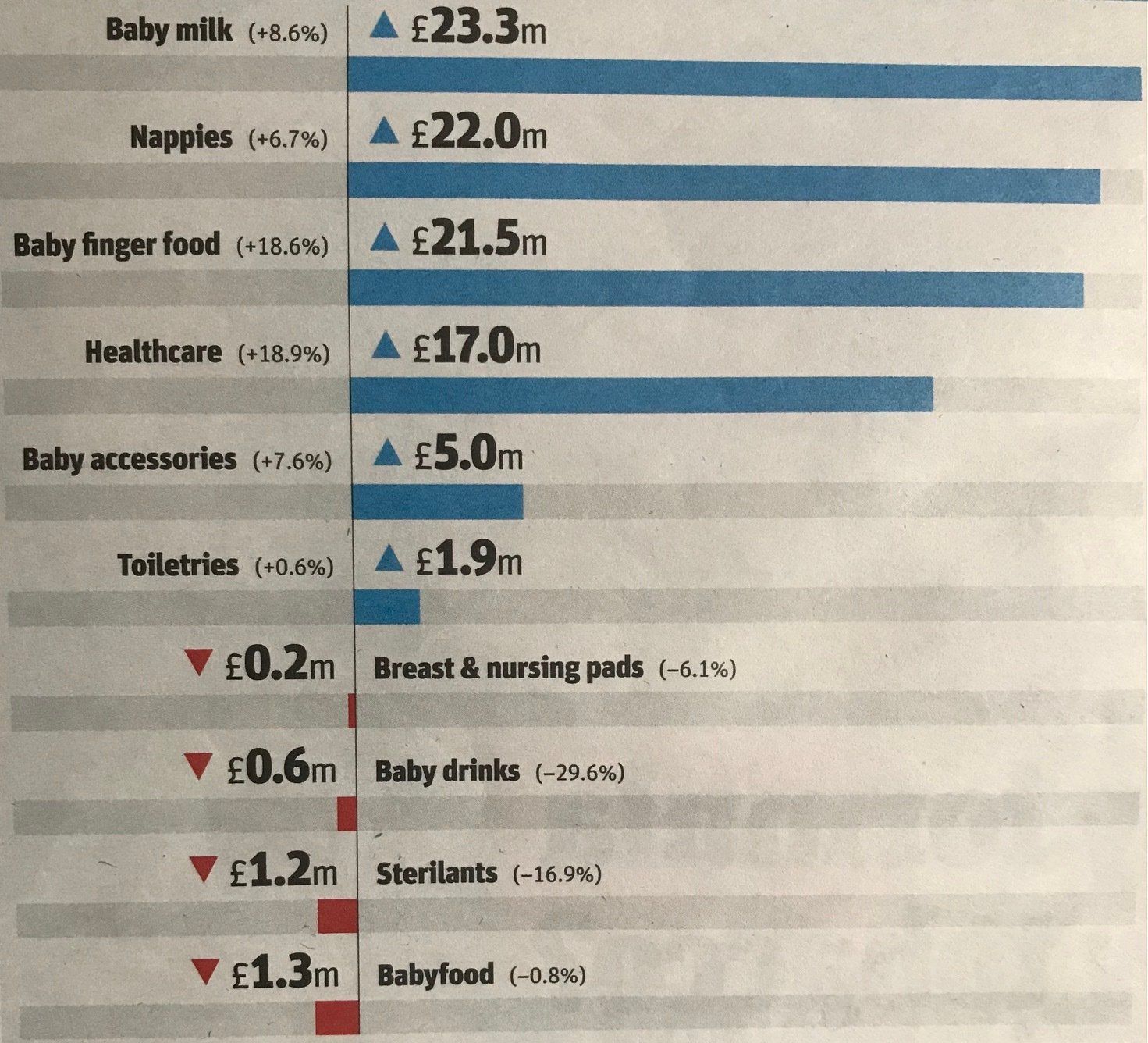

IBFM is the leading form of BMS, with the global formula market currently valued at over US$ 52bn (£44bn). 12 IBFM may indeed be inferior to human breast milk, but it does contain necessary vitamins, minerals, proteins and fats to meet the basic nutritional needs of babies. As a result of this, IBFM is a staple a majority consumer’s shopping basket with a newborn in the household. According to UK consumers data, IBFM grew by 8.6% to £295.8m, up by £23m, a resilient performance considering a challenging year. 13 Higher prices have placed pressure on parents, yet they have not served as a deterrent and as such has resulted in own brand labels (supermarket labels) growing a head of branded with own labels growing 6.8% in value against brands 6.2% increase. Irrespective of this, brand labels still outperformed own label 14.1%. 14 The growth in sales for branded IBFM is a recipient of the economic phenomenon of market demand, equating to value, necessity and in relation to branded labels, confidence, legacy and trust in the eyes of the consumer. However, this booming and bullish growth in revenue has drawn much controversy and scrutiny over the concerning marketing practices used by proprietors of leading brand labels to attain such gains at the expense of breast feeding and human breast milk.

In response to the current marketing tactics deployed by proprietors of IBFM & BMS, the World Health Assembly adopted the International Code of Marketing Breast Milk Substitutes (also referred to as The Code) in 1981. Within this charter, Article 5 states:

“…there should be no advertising or any form of promotion of BMS to the general public.”

Yet despite this article encoded within the charter, the promotion of BMS such as IBFM continues unperturbed and unyieldingly to concerning result uncovered by research undertaken by the WHO. According to the research finding of WHO; 4 million social media posts about infant feeding reached 2.47 billion people and generated more than 12 million likes, shares or comments. Around 264 BMS brand accounts posted content around 90 times per day and reached 229 million users and that social media posts that referenced BMS brands or products reached three times as many people as posts about breastfeeding, with people most likely to share or click on the posts relating to the former. 15 This is by no means an exhaustive list of the findings. As seen above, the prominent medium used by which IBFM proprietors use to deploy their marketing strategies utilises digital marketing and social media and online channels given than 80% women who reported seeing BMS advertisements reported having seen them online. 16 In addition to this, WHO’s research disclosed some of the marketing techniques implemented by IBFM proprietors and these included engaging in real time contact with women, joining or having access to virtual groups and “baby-clubs”, the use of social media influencers, the use of user-generated promotions via competitions and resorting to privately messaging and providing professional advice. Again, this is not an exhaustive list. The marketing techniques adopted and executed by IBFM proprietors have culminated into the core concerns surrounding their marketing practices. The findings from the WHO report have shown that:

i) BMS companies buy direct access to pregnant women and mothers in their most vulnerable moments from social media platforms and influencers.

ii) BMS companies are using strategies that aren’t recognised as advertising.

iii) That digital marketing can evade scrutiny from enforcement agencies. This could require the exploration of new approaches to code implementing regulation and enforcement. 17

To highlight these digital marketing practices is to say nothing of the irresponsible claims made by one BMS brand Danone, who was subsequently found to have broken the rules, by claiming that their Cow & Gate brand was easier to digest than regular cows milk as well as confusing infant formula and follow on formula. 18 Nestle too, along with Danone, have made dubious claims over the additional benefits of artificially created human milk oligosaccharides (HMO), essential to building a babies immune system, when added to their cow’s milk based infant milk. 19 With such misleading health claims marred by the backdrop of the controversy surrounding the marketing practices of IBFM proprietors marketing strategies that has seen the likes of articles “Could baby formula be the new tobacco?” it is fitting to find some rebuttal to the concerns and accusations levelled at the BMS brands. To this current perception and zeitgeist surrounding the practices of IBFM brands Olivier Lechanoine, VP of specialised nutrition at Danone UK & Ireland proffers a rebuttal. Mr. Lechanoine's opening gambit to the idea of equating formula milk to cigarettes as:

“…an unreasonable comparison.”

Furthermore, he acknowledges the benefits of breastfeeding, yet remind critics that breastfeeding is not an option for all families and that;

“…it is important that parents can make informed choices about the nutrition options that are right for their baby and situation. We need to support parents with factual, science-based nutritional information. This cannot be compared to cigarette marketing.” 20

Mr. Lechanoine concludes by affirming Danone’s commitment to contributing to sensible debate about the responsible marketing of baby formula and the protection of breastfeeding. As welcomed as these words are, there remain repercussions over the irresponsible claims and current marketing practices of IBFM.

One of leading repercussions is the “discouragement” of breastfeeding that currently costs the NHS £50m a year from preventable childhood illness and the reduction in the risk of developing breast cancer. 21 A secondary repercussion is the economic consequences associated with overregulation and fines. The stance to adopt here is not to throw the baby out with the bathwater. Instead, its better to acknowledge that any harsh sanctioning or disproportionate response to the current marketing of BMS brands could result in raised prices for the consumer causing cost-push inflation. The danger here is that some IBFM products may possess a degree of inelastic demand to certain households. To effectively enforce The Code’s charters, regulations or fines must be done in a sensible, equitable and measured fashion that accepts that digital marketing is a more cost effective and efficacious way of marketing than traditional means. After all, these BMS brands have a duty to their shareholders to deliver value or a return on their investment. The finally repercussion we’d put forward, is the concerns surrounding the increased cost of living and escalating inflationary environment that is hitting consumers hard. BMS brands can be vulnerable to food insecurity given the rising cost of constituents and fuel prices. With inflation projected to rise to 18% by early 2023, as of the time of writing, it highlights the concern of dependency on a sub-optimal nutritional product a caveat that human breast milk surmounts (by offering complete food security) and why breastfeeding should be encouraged and promoted. Despite the current climate and existing concerns there are solutions to trying to encourage breastfeeding more amidst the backdrop of BMS brands marketing tactics and pervasive digital presence within the UK.

Firstly, breastfeeding must be seen as a public health priority by policymakers and it would seem that such an attempt has been made. In 2015, the UK government mandated that every pregnant woman would receive five health checks from a registered health visitor. 22 In May of 2021 a recently updated Public Health England Guidance document entitled: Early years high impact area 3: Supporting breastfeeding was released to support families in breastfeeding and increasing the number of babies who are breastfed.

However, these initiatives and intention devised by public health bodies and policymakers are curtailed by cuts to supportive services. Therefore, the second solution is to reverse those cuts made to supportive services by increasing funding or reallocating ring-fenced capital and resources to help breastfeeding women. According to UK-wide Better Breastfeeding campaign, at least 44% of local authority areas in England and affected by recent cuts to breastfeeding services. These cuts further corroborate with other studies that saw 58% of respondent report that cuts to services (which included health visitors visits) as a barrier to breastfeeding. For completeness, 48% and 47% respondents reported closures of children centre services and cuts to infant feeding support groups irrespectively contributed to increasing the barriers of breastfeeding. 23 24

A third solution would involve the true and utter commitment to markedly tackling the long-term issues of socioeconomic implications, specifically health inequalities and cultural stigma within the UK. In relation to the former, the current cost of living and inflationary climate has placed more of an importance upon the influence of socioeconomics and food insecurity upon breastfeeding in a high income. For instance, taking qualitative findings from a fellow high-income country as Canada, suggest food insecurity may be root cause of breastfeeding cessation due to maternal fears of producing milk that is inadequate in quality and quantity. 25 The danger here, as alluded earlier, is the dependency of lower socioeconomic households upon IBFM something that contributes to infant food insecurity. In relation to the latter, point on cultural stigma as a barrier to breastfeeding, 63% of mothers would feel embarrassed breastfeeding in the presence of people they didn't know. A further 59% and 49% felt the same about doing so in front of partner’s family and siblings or wider family members respectively. 26 These figures highlight the need for more breastfeeding-friendly spaces as well as discussions and education, as a nation, on the subject of breastfeeding and doing so in public.

The final solution we propose to support breastfeeding entails the revision and reasonable implementation and enforcement of the codes stipulated within the international code of marketing of BMS. The intended achievement of the codes will most likely come to fruition if they serve as a proportional deterrent to over zealous marketing and the dissemination of unsubstantiated and grossly misleading claims. This must be a collaborative endeavour between public health bodies, policy-makers, charities and of course proprietors of IBFM and other BMS brands.

In conclusion and in answering the question posed we would subscribe to the idea that IBFM and BMS are not jeopardizing breastfeeding, though proportional regulation and enforcement is necessary to support and champion the optimal form of baby nutrition that is breastfeeding. Furthermore, it is worth acknowledging that whilst IBFM is suboptimal to human breastmilk, it remains irrefutably patient-centric. It supports the psychological welfare of the mother and meets the standard nutritional requirement of the baby. Both BMS and human breast milk can indeed “co exist” effectively. However, the current situation must be reviewed. Firstly, there must be a change in narrative towards the “demonisation” of IBFM and other BMS brands that make outlandish associations between IBFM and cigarettes for instance. To achieve a more constructive and productive dialogue on this subject that is conducive to the goal of ideal baby nutrition then a collaborative and reasonable environment must be fostered and maintained. Secondly, accountability and transparency from IBFM proprietors is crucial to ensure that mothers are able to make informed decisions regarding their baby’s nutrition based on scientifically substantiated data. Failing to do so should allow for the appropriate enforcing of the 1981 Code. A lack or lose of credibility is detrimental to the life science industry and in this case the pharma and nutritional companies. Finally, policymakers and health strategist within the UK government, local authorities and NHS must reverse cuts and again ring-fence capital and resources to support mothers with breastfeeding be it through visitations, local groups or educational material. Given the economic benefits of breastfeeding to the NHS and nutritional benefits to babies’, it calls for the continued reevaluation and financial support to be available and ever-present.

© All rights reserved, Nnadi’s Healthcare & Pharmaceuticals Limited, 2022.

Signposting:

LatchAid: https://latchaid.com/app - An informative app designed to t and encourage and support mothers breastfeeding with breastfeeding. There is useful information and statistics of interest too.

Medela: Breast milk composition: What’s in your breast milk? https://www.medela.com/breastfeeding/mums-journey/breast-milk-composition

National Breastfeeding Helpline: https://www.nationalbreastfeedinghelpline.org.uk/ - You can now contact them on Instagram. Contact number: 0300 100 0212.

NHS Breastfeeding Help and Support: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/baby/breastfeeding-and-bottle-feeding/breastfeeding/help-and-support/ - The website consists of a host of information and contact numbers and details of organisations that can help with breastfeeding.

Disclaimer: Recommendations made in the signpost are not endorsements nor do we have commercial interest or conflict of interest. We seek not to advertise any third party provider. If you have any questions please speak with your GP, midwife or local pharmacist.

References:

1. World Health Organisation (WHO). Breastfeeding. <https://www.who.int/health-topics/breastfeeding#tab=tab_1> accessed 26th August 2022.

2. Medela. Breast milk composition: What’s in your breast milk? < https://www.medela.com/breastfeeding/mums-journey/breast-milk-composition> accessed 26th August 2022.

3. Der G Batty GD Deary IJ. Effect of breast feeding on intelligence in children: prospective study, sibling pairs analysis and meta-analysis. BMJ (Clinc. Res. Ed.) 2006 333:945.

4. Oxford Population Health. University of Oxford. NPEU. New study finds evidence that breastfeeding directly supports children’s cognitive development. < https://www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/news/2248-new-study-finds-evidence-that-breastfeeding-directly-supports-children-s-cognitive-development> accessed 26th August 2022.

5. Binns C Lee M Low WY. The Long-Term Public Health Benefits of Breastfeeding. Asian Pac J Pub Health. 2016.

6. Brown R. Could baby formula be the new tobacco? The Grocer. 16th July 2022. William Reed.

7. Royal College of Midwives (RCM): J Griffiths. New Breastfeeding statistics for England. 2017. < https://www.rcm.org.uk/news-views/news/new-breastfeeding-statistics-for-england/> accessed 26th August 2022.

8. LatchAid. Breastfeeding in the UK. < https://latchaid.com/breastfeeding-in-the-uk> accessed 26th August 2022.

9. Ibid.

10. Davis N. Breastfeeding support services ‘failing mothers’ due to cuts. The Guardian. 2018 < https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2018/jul/27/breastfeeding-support-services-failing-mothers-due-to-cuts> accessed 26th August 2022.

11. Davis N. Low UK breastfeeding rates down to social pressures over routine and sleep. The Guardian 2016. < https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2016/sep/09/low-uk-breastfeeding-rates-down-to-social-pressures-over-routine-and-sleep> accessed 26th accessed 2022.

12. WHO. Scope and impact digital marketing strategies for promoting breast milk substitutes. 2022. < https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/353604/9789240046085-eng.pdf?sequence=2> accessed 26th August 2022.

13. Ibid 6, - Kantar 52 w/e 15 May 2022.

14. Ibid 6

15. Ibid 12

16. Ibid

17. Ibid.

18. Ibid 6

19. Ibid

20. Ibid

21. Ibid 8

22. Removing the Barriers to Breastfeeding: A Call to Action. How Removing Barriers Can Give Babies Across The UK The Best Start in Life. Unicef United Kingdom The Baby Friendly initiative. https://www.unicef.org.uk/babyfriendly/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2017/07/Barriers-to-Breastfeeding-Briefing-The-Baby-Friendly-Initiative.pdf accessed 01st September 2022.

23. Ibid 8.

24. Ibid 22.

25. Dinour LM Rivera Rodas EI Amutah-Onukagha NN Doamekpor LA. The role of prenatal food insecurity on breastfeeding behaviours: findings from the United States pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system. Int Breastfeeding J. 2020.15:30

26. Ibid 22.