Tipping Point: Body Positivity vs. Weight Management

“Be yourself”, “Love who you are” and “Never apologise for being you” are common self affirmations associated with wellbeing but can extend to body positivity. The fashion, beauty and sporting industry are leading the vanguard on the encouragement of body positivity in the name of representation and diversity of body types. This is indeed a good thing and very much welcomed. However, there must be a sense of awareness and caution to the indirect promotion of any health implications, in particularly prediabetes. This article will explore the dichotomy between social norms of body positivity versus clinical (health) concerns surrounding body positivity. This article will cover, to an extent, the relationship and impact of body positivity and body image may have upon mental health, healthy weight management and how best to beat prediabetes and Type-2 diabetes. Finally, we shall cover how a healthy weight is calculated, its significance and metabolic difference between individuals. This article will not cover nor engage in any post-discussion or debate on the topic of body positivity in relation to attraction. From a medical viewpoint, attraction is a subjective, fickle and not germane to this article. Given the sensitivity of the subject it would be appropriate to cover the impact on mental health and psychological well-being.

Body positivity is inextricably linked to our self-image, which is key to our sense of identity. Simply put, how we look equates to how we feel. The perpetuation and desirability in the pursuit of the “perfect body” arises primarily from various forms of consumption. Common sources and outlets of this category include; Hollywood, Reality TV, ITV’s mega-successful Love Island franchise and Meta’s Instagram, all offering a window into innocuous entertainment, whilst showcasing the latest beauty trends that go on to become the societal standard. However, this harmless form of entertainment ceases to be so when the perpetuated trends by A-listers, well-known celebrities or recognised public figures (devoid of malice or agenda on their part), are, perceived as unattainable. It is this realisation that is impactful and leaves a detrimental effect on the most vulnerable members of the public on the uses of body image- teens and adolescents. The data to support this is worrying.

According to UK survey of 11-16 years olds conducted by

Be Real found that 79% said how they look is important to them. Over half (52%) often worried about how they looked. 1 In a survey of young people aged 13-19, 35% said their body images cause them to ‘often’ or ‘always’ worry. Research has shown that girls are more likely to be dissatisfied with their appearance an their weight than boys.2 3 In a survey by Mental Health Foundation, 46% of girls reported that their body image caused them to worry ‘often’ or ‘always’ compared to 25% of boys.4 In addition to this UK survey by

Be Real, targeted at UK adolescents, it was revealed that 36% agreed they would do whatever it took to look good with 57% saying they had considered going on a diet and 10% saying they had considered cosmetic surgery.5 Disturbingly among secondary school boys, 10% said they would consider taking steroids to achieve their goals.6 Through these surveys, young people have expressed that body image is a substantial concern. Body satisfaction and a pressure to be thin is linked to depressive symptoms such as anxiety disorders (social anxiety or panic disorder) particularly in those children who do not match societal views of the ideal body.7 8 9 Possessing a poor body image may also prevent young people from engaging in healthy behaviours, as studies have found that children with poor body image are less likely to take part in physical activity. Survey data has shown that 36% of girls and 24% of boys avoided taking part in activities like physical exercise/physical education (P.E.) due to worries about their appearance. Body image is a substantial concern identified by 16-25 year olds and is the third biggest challenge currently causing harm to young people behind a lack of employment opportunities and failure to succeed within the education system being the first two.10

Body positivity is a social movement with the rationale of addressing and combating these concerns and issues surrounding body image and their effects on people’s mental health, predominantly young people. Body positivity intends to be an inclusive movement focused on celebrating and welcoming all body types, regardless of size, shape, skin tone, gender, and physical abilities. It is a movement that seeks to rewrite present beauty standards deemed as the norm. This movement has not gone unnoticed by corporations, one of which is the sporting apparel giant Nike. In 2019, Nike introduced a plus-sized mannequin to its London flagship store, NikeTown. This move was not without fierce debate and controversy. One side welcomed the sporting giants decision calling it truly inclusive and dispelling erroneous and outdated preconceived notions about plus-size women being unable to participate in physical activity, whilst the other side argues that it perpetuates a “dangerous lie” encouraging people to deny health risks related to obesity. 11 12 The opposing views held by both camps on the matter of plus size mannequins depicts clearly the contentious dichotomy between social norms versus clinical health concerns. We shall now explore the latter viewpoint.

There currently exists a silent obesity pandemic. Latest figures recorded by The World Health Organisation (WHO) show that obesity has tripled since 1975.13 This observation is far from hyperbole as looking closer to home there exists an obesity crisis across Europe, with the UK being one of the nations suffering the brunt of this crisis. From the data aggregated from the study, the UK is considered a nation at high risk. The UK ranked 3rd for obese adults, 12th for childhood obesity, 8th for obesity in children and adolescents and 4th on a chart of “The fattest nations in the EU”.14 What’s more, the WHO warns that the European obesity crisis is responsible for 1.2 million deaths a year. Obesity and overweight contributes to a myriad of health issues including fatty liver disease, breathing difficulties and mobility issues just to name a few. According to data from Cancer Research UK, obesity and overweight are the 2nd largest cause of cancer behind smoking in the UK. More pertinently, obese or overweight individuals are more likely to be prediabetic and on the cusp of becoming diabetic (Type-2), and heading into, if not already experiencing, metabolic syndrome; a cluster of common pathologies such as insulin insensitivity and hypertension. The link between T2D and heart disease is well-established. The unchallenged acceptance surrounding body positivity, from a medical perspective, is financially detrimental to our NHS due to the cost of treatment and complications that arise from a chronic disease. Furthermore, a chronic illness sweeping amongst a population will undoubtedly affect a nations economy negatively striking directly at our labour force and productivity. We strive for a healthier nation and in order to do so we must promote, support and provide education on the importance of achieving an individuals’ ideal body weight as opposed to an ideal or socially accepted body type.

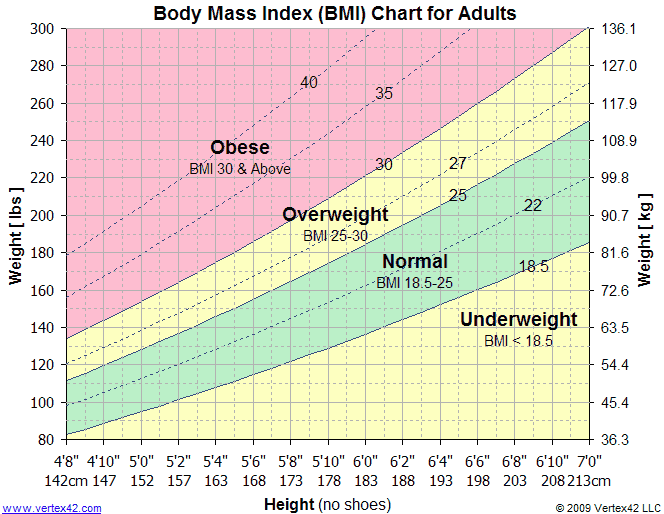

The gold standard for identifying an individual’s body weight is by calculating their body mass index (BMI). The BMI is calculated by dividing a person’s weight in kilograms (kg) by their height in metres squared. An ideal BMI ranges between 18.5 to 24.9. An individual deemed obese would have a range between 30 to 39.9. The choice to use a BMI range is not without its critics and caveats. For instance, muscular and athletic people such as rugby union players and heavyweight boxers fall victim to the irony that their BMI range classifying them as overweight, whilst they are in fact a health weight. The discrepancy arises due to muscle being denser than fat.15 Equally your ethnicity can skew your BMI reading, as some ethnic groups such as South Asians are more susceptible to some health problems such as diabetes with a BMI of 23, which is usually considered healthy.16 Finally, on the theme of caveats, research has shown that a grey zone exists with people who are obese but metabolically healthy, meaning they have healthy cholesterol and blood sugar levels as well as normal blood pressure. Despite the contradictory nature of this finding, medical advice supported by clinical data, suggest losing weight may be more beneficial for you.17 It is for this reason, we encourage all people, men and women irrespective of size to increase their physical activity in a manner that is effective and comfortable to them.

In closing, we have looked at the subject of body positivity its rationale as a social movement, its importance and impact on teen and adolescent mental health. We have looked at this movement that has been gaining traction against the backdrop of an obesity crisis in Europe. We have also presented two polarizing and at times polemic points of views relating to body positivity and the plus-size model debate. Our contribution and stance on this debate comes purely from a medical angle. To reiterate we care not about “attractiveness”. This is a superficial at least and subjective at most. We acknowledge and respect the latter. However, neither is central to our source of concern on the topic. Our concern resides with improving and maintaining physiological well-being and any threat to the quality of life or life itself through prediabetes or the development of T2D. We reject the acceptance, normalisation and at times acquiescence of an individual’s weight being clinically unhealthy, but champion the necessity and ideals for an individual to retain a degree of responsibility and effort in managing their health to give them the best quality of life. This is what we support wholeheartedly. As a healthcare & pharmaceutical company, it would be grossly irresponsible to suggest the opposite. Our responsibility also extends to ensuring we do not criticise or crush any genuine initiative or attempts that may help individuals take their first step to losing that excess weight. Whilst support those individuals we aim to move the conversation towards positive thinking and positive actions towards good health and the awareness of the dangers prediabetes can pose.

© All rights reserved, Nnadi’s Healthcare & Pharmaceuticals Limited, 2022.

Reference:

1. Be Real. Somebody Like Me: A report investigating the impact of body image anxiety on young people in the UK. [Internet]. 2017. Available from: https://www.berealcampaign.co.uk/research/somebody-like-me

2. Delfabbro PH, Winefield AH, Anderson S, Hammarstrom A, Winefield H. Body image and psychological well-being in adolescents: The relationship between gender and school type. J Genet Psychol. 2011 Jan 25;172(1):67–

3. Kenny U, Sullivan L, Callaghan M, Molcho M, Kelly C. The relationship between cyberbullying and friendship dynamics on adolescent body dissatisfaction: A cross-sectional study. J Health Psychol. 2018 Mar 5;23(4):629–39.