Faith & Medicine: How Understanding the Relationship between Faith and Western Medicine to Better Improve Primary Care Health.

In the Western world, and specifically to Western medicine (allopathic medicine), faith commonly tends to meet medicine at the intersect of “last resort”. Sporting analogies vividly depict such dire occasions, the “Hail Mary Pass” of American Football, “The bottom of the ninth” of American baseball or “90 minutes plus stoppage time” in football (soccer). Once the game plans and tactics have been tried and exhausted to no avail, the game of the respective sports take on a more urgent, opportunistic and hopeful complexion for the teams involved. This scenario is very much reminiscent of when medicine has been deployed as the opening gambit to tackle ill health only to find it is yielding little to no dividends towards improving to the patient’s health or condition. In this situation desperate times call for desperate measures and in the face of such desperation faith is sought and clung onto. Faith and medicine enjoy a polarising duality; Spirituality versus Science, “The Unseen” versus “The Proven”, subjectivity versus objectivity, belief versus evidence. Even in the face of this presented incompatibility between Faith and Medicine, there resides a common thread that unifies both. Patients. This article will look at the importance of acknowledging faith in medicine and the role faith plays in healthcare, particularly in primary care.

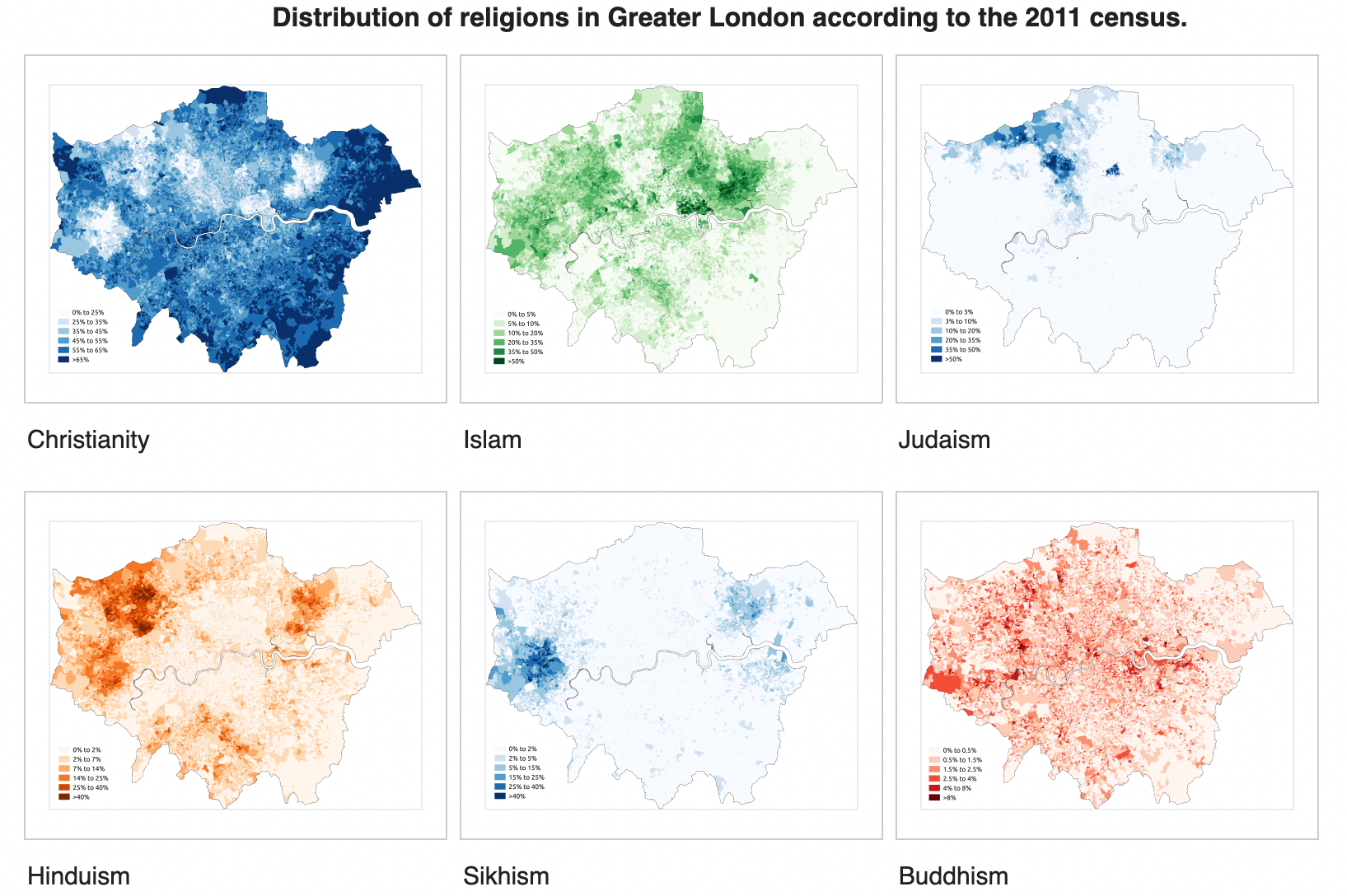

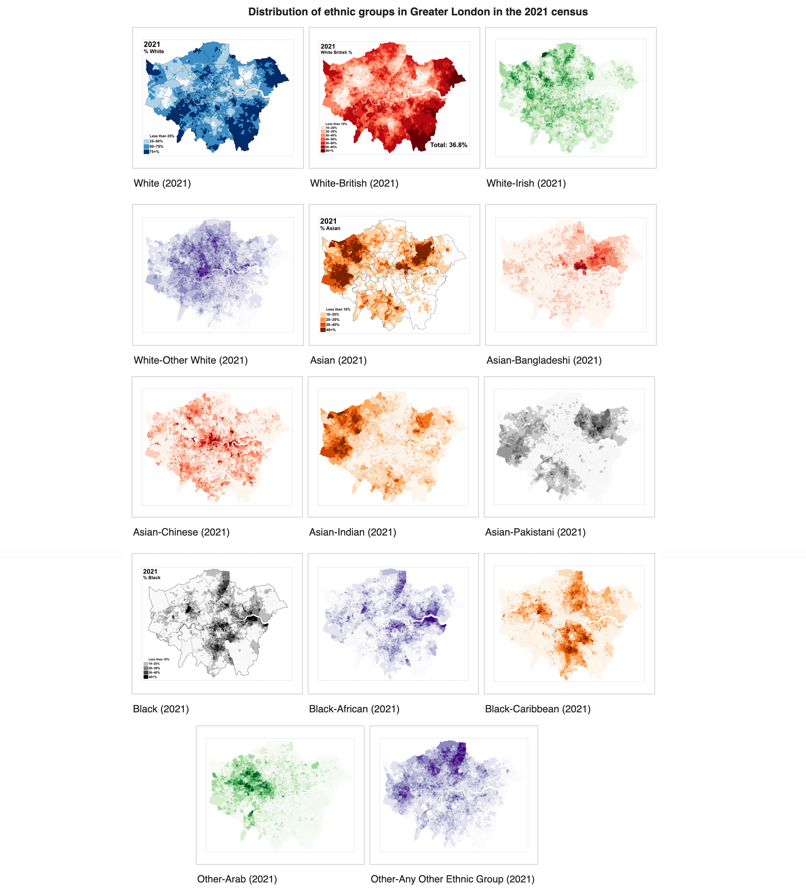

The opening sentiment of this article on the relationship between Faith and Medicine may appear somewhat flippant and reductive. For some patients, faith does not follow a sense of hopelessness or vulnerability. Rather faith, in their respective religion, is their North Star. Their compass in navigating their day-to-day life of which, their healthcare needs are no different. Faith is central to the identity of an individual and for the collective community and demographic. An understanding of a patient’s faith in the healthcare sector is necessary in a multicultural country like the UK and more so in her multicultural major cities such as London. According to the latest data from the ONS (Office for National Statistics) 2021 Census, Christianity remains the largest religion in London with 40.66%, with Islam, Hinduism, Judaism, Sikhism and Buddhism following in sequential order at 14.99%, 5.15%, 1.65%, 1.64% and 0.99% respectively 1. When making an eyeball comparison of the religions distribution chart from the ONS 2011 Census against the ethnic group distribution chart from the 2021 Census, it provides a quantitative and qualitative insight into where specific demographics are situated across London 2. For instance you will find a majority of the Black Afro-Caribbean demographic in South East London an area with a high number of individuals identify as Christians, Asian-Indian in West London, an area where a large majority identify as Hindus and Sikhs, Asian Pakistanis far West & East London where Islam is the dominant religion and individuals who identify as Jewish are predominantly situated in the North and North West London area.

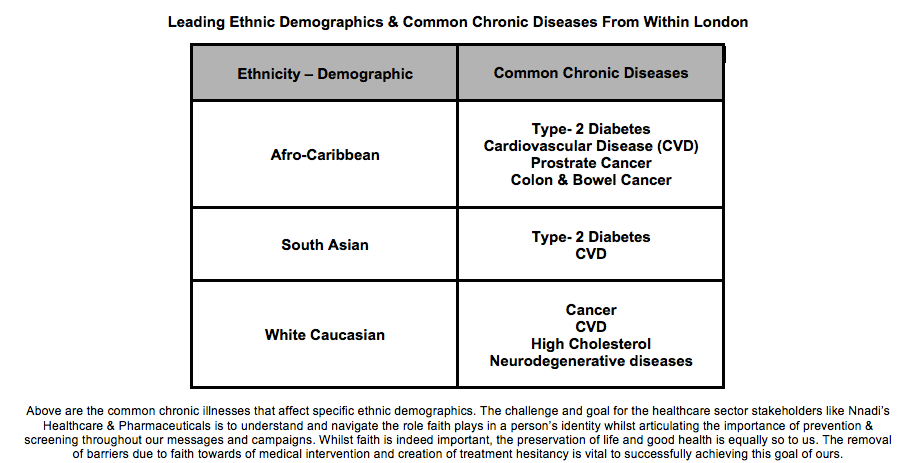

A majority people who identify within an ethnic group demographic will have some connection to a religion, which plays an integral part to shaping their culture as well as their faith. This is of significance as these individuals then to be those as risk of preventative chronic disease of which the health outcome can be a poor prognosis. The data derived from the charts below will form the basis for strategies that are to be deployed in meeting the clinical needs of the multicultural demographic in London.

Source: Wikipedia , ONS 2011

Source: Wikipedia , ONS 2021

A failure to acknowledge the role of faith in multicultural societies and communities can result in frustrated and unsuccessful primary care engagements with a healthcare message that does not resonate with the intended audience. To avoid the notion that faith may act as a barrier to the delivery of healthcare, it would serve us well to understand the leading religions’ stance on healthcare through respected holy books and central philosophies of practiced religions in the UK.

Sacred scripture and philosophy have provided structure and guidance to the practicing of an individual’s faith. We’ll now look at the leading text across the leading religions. Beginning with Christianity, The Bible in James Chapter 5 verses 14-15 (New International Version (NIV)):

“14 Is anyone among you sick? Let them call the elders of the church to pray over them and anoint them with oil in the name of the Lord. 15And the prayer offered in faith will make the sick person well; the Lord will raise them up. If they have sinned, they will be forgiven.”

This passage calls to mind the holy sacrament within Roman Catholicism of the Last Rite, Yet in Luke 5:31 we find the following passage:

“It is not the healthy who need a doctor, but the sick.”

In this former passage we see the affirmation of faith and prayers towards ill health in Christianity, whilst the words of Jesus depict the pragmatic acknowledgement of a doctor for those afflicted with ill health.

In Judaism, drawing upon the Torah it is believed that God makes people sick and only He can heal them. This is found in the following books of scripture:

Exodus: 15:26:

“If you will heed the Lord your God diligently.

Then I will not bring upon you any of the diseases that I brought upon the Egyptians, for I the Lord am your healer.”

And in Deuteronomy: 32: 39:

“I deal death and give life, I wounded and I will heal”

Drawing upon the interpretation of the Talmud (Rabbinic debates and literature from the 2nd-5th Century based upon the teaching of the Torah) this sentiment of God’s central role in health is consolidated in the following interpretation by Rabbis

And Hullin 7b:

“A person does not injure his finger below unless it is decreed above.”

However, in the book of Ben Shira (Sirach, Ecclesiaticus), it is believed that with prayer (God), sacrifice and visiting a doctor as stated in Chapter 38 verses 1-4:

“1 Give doctors the honour they deserve, for the Lord gave them their work to do.

2 Their skill came from the Most High, and kings reward them for it.

3

Their knowledge gives them a position of importance, and powerful people hold them in high regard.

4 The Lord created medicines from the earth, and a sensible person will not hesitate to use them.”

The evolution towards the role that doctors play in medicine within Judaism continues with the acknowledgement that doctors were vital in society according to a baraita in Shanhedrin (17b) before arriving to the notion that it is Mitzvah (a good deed) for a doctor to heal people as proposed by the teachings of Maimonides. 1

Within the teachings of Islam, there exists two hadiths of significance. The first is that which the Prophet Muhammed in which he states;

“There are two blessings which many people do not appreciate: Health and leisure.” 2

This is appreciation for the gift of health within Islam is emphasised by the hadith as narrated by Usamah Bin Shareek that encourages the use of medicines to treat ailments:

‘I was with the Prophet (PBUH), and some Arabs came to him asking, “O Messenger of Allah, should we take medicines for any disease?” He said, “Yes, O You servants of Allah take medicine as Allah has not created a disease without creating a cure except for one.” They asked which one. He replied “old age.” 2

In Hinduism, based on Dharma traditions spirituality is dependent on health and wellness and that health and wellness is dependent on spirituality.5 Therefore, Hinduism’s ideology that health and spirituality are interwoven encourages individuals to adopt a preventative approach to maintaining good health by developing good daily habits.6 7 In Sikhism, there is no restriction on taking medicines and in fact it is even encouraged.8 Finally in Buddhism, Buddhists have a positive attitude towards seeking medical advice and taking medicine that helps. This does not breach the fifth precept that forbids the consumption of intoxicating drink or drugs, which cloud the mind. Even if a prescribed medicine that may be intoxicating is administered, Buddhists believe this is acceptable as the objective of the medication is to restore good health.

What we can learn from these major, yet differing religions, is their reverence for their spiritual doctrines and practices, whilst adopting a sense of pragmatism towards Western medicine. This acceptance towards medical advice & intervention dispels the idea, in theory, that religion & faith pose a barrier to accessing healthcare. The significance of these findings regarding the relationship between faith and medicine, can contribute positively to addressing the issues such as health inequality in primary care.

Within the NHS, health inequality is defined as unfair and avoidable differences in health across the population between different groups within society.9 These differences can be attributed to socioeconomic status, which tends to be a determining factor. Looking at health inequality closer, there is ethnicity health, which can be defined as health needs, conditions and trends commonly identified in specific demographic that share cultural factors such as language, diet, religion, ancestry and physical features.10 Within ethnicity health, it is more likely one would come across specific attitudes amongst an ethnic demographic. An ideal case study depicting ethnic health was seen around the disproportionate impact COVID-19 had on black and minority ethnic groups. A Lancet report found that those from ethnic minority groups during the 2nd wave of the coronavirus pandemic were more likely to test positive for COVID-19, become severely ill and die.11 To prevent future outcomes as seen from the above report, primary strategies and campaigns must capitalise on the accepted pragmatism of major religions in order to deliver a message that resonates successfully with the attended ethnic demographic. The message must be one that contains either or both the importance of prevention and adherence.

Prevention and adherence are central concepts behind with key roles to play behind any strategy for a successful primary care campaign. One of the NHS’ objectives as part of their Long Term Plan initiative is prevention.12 Preventative medicine reduces the burden placed on secondary care with avoidable hospital admissions as well as increasing better health outcomes. This approach ties in with ethnicity health and no better example of this can be seen than in the NHS’ efforts towards tackling Type 2 Diabetes, which sees Black Afro-Caribbean and South Asians minorities two to four times more likely to develop Type 2 Diabetes.13. Aside from preventative measures, medicine adherence not only seeks to save NHS London losing £39.4 million a year from unused prescription medicine, it can improve health outcome especially in hard to reach ethnic demographics too.14 This is pertinent as those from a religious background may decide to stop medication (without consulting a healthcare profession) due to their faith and spirituality.15 A consequence of this decision, would most likely result in a person spending longer in primary care (being seen again by their prescriber and taking up time), being admitted to hospital (creating pressure on secondary care resources) or their condition deteriorating. These scenarios place a burden on already stretched NHS resources, something we seek to reduce and avoid. Whilst prevention and adherence are vital in the inclusion of any message there must also be a commitment to restoring confidence in the healthcare system. This includes all stakeholders associated with healthcare in the UK. It is essential that the healthcare sector consistently demonstrates acts of confidence in order to gradually and eventually gain the trust of the public, a vital component in extinguishing hesitancy towards medical intervention.

In conclusion, faith and medicine may be perceived as opposing constructs that are poles apart, however they are indeed drawn to people. This is what unifies them. For those who are religious, faith forms their very identity and failure to acknowledge this result in a frayed relationship between this demographic and the healthcare sector. Knowing there exists a degree of pragmatism amongst major religions towards healthcare and medicine, it is vital for stakeholders like Nnadi’s Healthcare & Pharmaceuticals to gain the public’s trust through consistent confidence whilst delivering a message of prevention & adherence in a manner that aligns with members of a religious demographic. The objective is to not only contribute to address health inequality, particularly seen by ethnic demographics, but also improve health outcomes at the primary care level overall.

Nnadi’s Healthcare & Pharmaceuticals will strive to keep the relationship between faith medicine in mind and with all subsequent engagements and initiatives with the public.

© All rights reserved, Nnadi’s Healthcare & Pharmaceuticals Limited, 2024. Thumbnail photo by Corey Collins.

References:

1. Wikipedia: Religion in London: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Religion_in_London [accessed 23rd November 2024]

2. Wikipedia: Demographics of London. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Demographics_of_London [accessed 23rd November 2024]

3. The Schecter Instititues. What is the Jewish Attitude Towards Medicine? – Rabbi Professor David Golinkin. https://schechter.edu/what-is-the-jewish-attitude-towards-medicine-responsa-in-a-moment-volume-1-issue-no-3-november-2006/ [accessed 19th November 2024)

4. Assad S, Niazi AK, Assah,S. Health and Islam. J Midlife Health 2013 Jan-Mar;4(1):65. doi: 10.4103/0976-7800.109645

5. In Hinduism, What is the Relationship between Spirituality and Health?- Suhag Shukla. Hindu American. https://www.hinduamerican.org/blog/hinduism-and-health [accessed 19th November 2024]

6.Ibid.

7. Naidoo. T. Health and health care--a Hindu perspective. Med Law. 1989 7(6):643-7

8. Sikhism: A Healthcare Worker’s Guide: https://www.sikhcoalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Sikhism-Healthcare-Guide-Electronic.pdf [accessed 21st November 2024]

9.NHS Trust. Weston Area Health. Buddhism. https://www.waht.nhs.uk/en-GB/Our-Services1/Non-Clinical-Services1/Chapel/Faith-and-Culture/Buddhism/ [accessed 21st November 2024]

10. NHS England. Equality, Diversity and Health Inequalities. https://www.england.nhs.uk/about/equality/equality-hub/national-healthcare-inequalities-improvement-programme/what-are-healthcare-inequalities/ [accessed 21st November 2024]

11. Mathur R Rentsch CT Morton CE Hulme WJ Schultze A MacKenna B. Ethnic differences in SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19-related hospitalisation, intensive care unit admission, and death in 17 million adults in England: an observational cohort study using the OpenSAFELY platform. Lancet. 2021; 39710286: 1711-1724

12. NHS Long Term Plan: Prevention. NHS https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/areas-of-work/prevention/ [accessed 23rd November 2024]

13. Diabetes UK. Type 2 Diabetes Know Your Risk. Prediabetes. https://www.diabetes.org.uk/about-diabetes/type-2-diabetes/prediabetes [accessed 24th November 2024]

14. Waste Medicine Campaign- York Road Surgery, Ilford. . https://www.yorksurgeryilford.nhs.uk/2023/11/09/waste-medicine-campaign/ [accessed 23rd November 2024]

15. Health Experience Insights (hexi). Mental health: ethnic minority experiences. The role faith, spirituality & religion for people with mental health problems. University of Oxford.

https://hexi.ox.ac.uk/mental-health-ethnic-minority-experiences/the-role-of-faith-spirituality-religion-for-people-with-mental-health-problems [accessed 24th November 2024]