Prescriptions to the Moon? The Growing Cost of NHS Prescriptions in England.

17 June 2021

“Crypto to the moon!” This is the bullish, and at times immensely speculative, sentiment adopted and exalted by impassioned cryptocurrency holders whenever the price of digital currencies rises exorbitantly, more so during this pandemic. It would seem that the trend observed in rallying cryptocurrency market prices are somewhat reflective, but to differing extents, of the rising price in NHS prescriptions for patients in England.

As of April 1st 2021, prescription prices in England are set to rise with the cost of an NHS prescription (per item) rising from £9.15 to £9.35 (an increase of 2.2%) and the NHS pre-payment certificate rising from £105.90 to £108.10 (an increase of 2.1%). 1

It is believed that these increases are in line with inflation. At this point, it should be mention that those exempt from NHS prescription payment; full-time students, over 60’s, those on income support and those with chronic long-term conditions such as diabetes etc., will be unaffected by these price increases. However, the timing of said increases, given the current economic landscape, shines a light on this re-emerging topic, its economic implications to both the public and the NHS, whilst calling for the scrutinising of NHS spending and the development of strategies towards the NHS devising, operating and maintaining an economically sustainable model for the delivery of care in the years to come.

The year 2020 was chaotic and punishing to the fortunes and aspirations of the UK economy, families and individuals. These new NHS prescription charges find themselves being introduced into a reeling economy that has seen unemployment rise (despite the government supporting an estimated 4.5 million employees via Job Retention Scheme, otherwise known as Furlough, the initiative has been deemed a stay of execution prolonging the inevitable), the deterioration of the labour market, an increase in redundancy claims and looming uncertainty surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact upon inflation. 2 3

What’s more, climbing prescription prices affect a grey area of population estimated to be in the region 300,000 people labelled as the “The Forgotten Unemployed”. This cohort consists of people, predominantly young men and older women; 55-64 years of age, who are without jobs or on very low wages and not claiming benefits they are entitled to. 4

Sadly, it is most likely that such a group would either retain its numbers or increase in size due to the pandemic’s impact on the economy. In addition to this demographic, there exists patients who are required to pay for long-term chronic illnesses such as Parkinson’s Disease (PD) and Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IPD). The concerns around NHS prescription prices are certainly founded given that latest projections indicate the price of an NHS prescription will exceed the £10 mark, costing an NHS patient in England £10.15 (per item) by 2025. 5

In order to address and arrest the rise of NHS prescription on this forecasted trajectory in England, it is essential to understand the economics surrounding this topic.

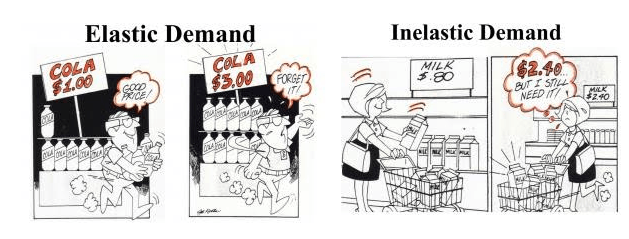

Economics, in particularly microeconomics, is the study of human behaviour, specifically an individual’s decision-making in relation to demand and scarce resources with an alternative use. In such a system, price governs consumer behavior and herein lies the concern with NHS prescriptions potentially and on course to exceeding the £10 mark. It will influence, and hence, negatively affect a patient’s health-seeking behavior. The common adage “Health is wealth” would not be adhered to due to the commonly observed economic phenomenon of price elasticity. Elasticity can be defined as the sensitivity of a given products demand in relation to fluctuation in price, thereby deeming a product as elastic (meaning demand is sensitive to price increase) or inelastic (meaning demand is not sensitive to price increase). Applying this to principle and economic observation to that of prescription prices, a prescription, in the eyes of a patient may be viewed as elastic and not as inelastic as the common adage professes. Therefore, a price increase could potentially discourage a patient from seeing their GP or other NHS prescribing healthcare professional or fulfilling a prescription as a result of price.

As from the cartoon above, a can of cola valued at $1 is reasonably priced. However, should the price increase to $3 consumers would shun the can of cola. On the other hand, milk once priced at 80c, now costing $2.40 would not cause for consumers to shun milk. The difference in behaviour to price, is defined by the consumers perception of value or necessity to them. This is what determines demand with a marketplace.

In light of pricing influence, another contributory factor governing patient behaviour and decision-making are socioeconomic pressures. A patient in this situation is met with the dilemma of opportunity cost, which equates to making a decision between the choice of obtaining a completed prescription or being short on a personal loan repayment for that month, or having an attenuated shopping budget or skipping a meal. Opportunity cost is the loss of other alternatives when one alternative is chosen. 6

Such a dilemma bears both short-term and long-term consequences. In the short-term, poor health choices are made by patients that result in poor health outcomes. In the long-term, the consequences are not only visited upon the patient they are visited upon the NHS, thus there exists a long-term pharmacoeconomic implication in rising NHS prescription costs in England.

Prescriptions aid with the management or treatment of ailments and disease and can work as a form of preventative medicine, in a more specific fashion than their over-the-counter (OTC) medicines counterparts, in a primary care setting. If we take the example of a simple acute skin infection (cellulitis) of a leg, failure to address this short-term can potentially amount to a significant cost in the long-term. To perform a cost-benefit analysis of treatment within a primary care setting as opposed to treatment in a secondary care setting for such an infection, one would need to consider the following components in their analysis. The cost of 7-day course of treatment with a two-item prescription for a 28 box of flucloxacillin 250mg, four times a day (QDS) and 15g tube of 2% fusidic acid, QDS at a price of £1.67 and £1.92 respectively. 7

Assuming the patient does not present to their GP or opts not to fulfill their prescription and the infection becomes worse, the patient may then be admitted to hospital where upon admission a bed costs on average £222. 8

Once admitted the clinical team will begin a course of treatment involving intravenous (IV) flucloxacillin 2g, every 6 hours QDS at a cost of £6 per 2g vial equating to £24 for a single day of treatment in a hospital care setting. 9&nsp;&nsp;10

In total, treatment at this stage would cost the NHS a minimum of £246 in comparison to £3.59 at primary care. Should the patient continue in prolonging to seek treatment and delay therapeutic intervention through a prescription, the infection can lead to necrotizing fasciitis and in extreme cases surgical intervention would supersede therapeutic intervention in order to improve patient prognosis (in order to avoid death), a single limb amputation would be the treatment of choice.

Surgery of this nature depending on complexity, can range from £5,776- £19,751. 11

These costs say nothing of the aftercare support via NHS occupational therapist, which would set the overall cost soaring. Nevertheless, it demonstrates the vast cost, from just under £4 to almost £20,000, a cost benefit analysis would take have to take this into consideration in its calculation in the treating of a simple infection if caught early in cellulitis. Acknowledging the long-term pharmacoeconomic complications to the NHS, it should serve to galvanise all involved stakeholders to work towards strategies, with the rationale of minimising costs from health complications through a modern and sustainable prescription charge system for England.

On the topic of prescription charges, there exist two schools of thought with opposing arguments. The leading argument for abolishing prescription charges, suggests that such charges create a false economy and is a tax on the sick based on an obsolete and unjust exemptions list that has not been amended since 1968. 12

The leading argument against abolishing prescription charges, propose the reformation of the current exemption list and charging policy, as abolishing prescription charges would cost an estimated £600m. The proposed reformation draws on the findings from the Baker’s Health & Social Care Report Commission, commissioned in 2014. The report acknowledges that a charge of £9 an item was too high, suggested reducing prescription charges by 2/3, and that by reducing the exemptions, but leaving a cap in place for prescription charges, could raise more money than the current charge (this is in accordance to prescription charges in 2014), hence reducing the burden on the less well off who do pay, whilst seeing those who are not currently paying under this system, pay something. 13

Despite these proposals, there may indeed be resistance, namely politically, over the implementation of the suggested removal of a blanket exemption for older people, as this would not be a “vote winner”.

Scrapping prescription charges is the most popular and far easier than reforming the current system, but to do so at the tune of £600m calls for serious consideration. The Barker Report presents a spectrum of options for funding new settlements including charges for healthcare, cuts in other areas of public spending and higher taxation.

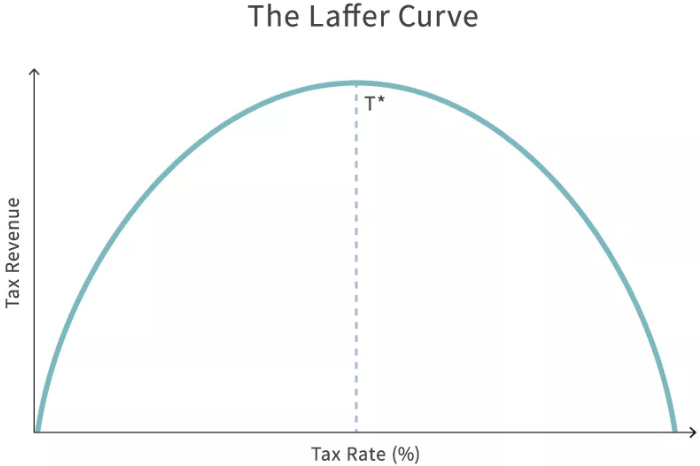

Although this approach makes sense theoretically, the practical application of increased taxation would succumb to the same economic fallacies of other economic policies drafted with the utmost altruistic intentions to address short-term issues whilst neglecting the long-term consequences. As American economist Arthur Laffer once said “When you cut the highest rates on the highest income earners government gets money from them”. This theory is best depicted in Laffer’s Curve.

As you can see from the diagram there is a point at which raising tax rate may increase revenue. However, and as it is quite often the case tax rate beyond a certain threshold results in a reduction in tax revenue, defeating the initial intended purpose of raising taxation.

We would support the prioritisation of savings over higher taxation as means to arrest escalating prescription prices in England. It was purported by an independent auditor, that the NHS wastes £7.6bn a year, an analysis that is somewhat corroborated by the Lord Carter report which identified and called for £5bn of savings to be made annually by 2020. 14 15

A final finding that reinforces our stance on prioritising savings over taxation is the conclusion arrived at by the National Audit Office (NAO), who concluded that the NHS is not financially sustainable. 16

Furthermore, this conclusion echoes the same admonition made back by the NOA in 2019 when highlighting that then, Prime minister Theresa May’s cabinet’s pledge of £20.5bn towards fixing the crisis within the NHS would not suffice. Taking into account the projected level of waste amounting £7.6bn and the conclusions of the NAO, it would question the sagacity of implementing a strategy to address this crisis by requesting higher taxation. A justification for introducing more money into such a system in its current form is improbable and indefensible. Moreover an increase in national contribution, off the back end of an economically challenging time for a majority of citizens within England, would be most tone-deaf.

The prioritisation of savings, and to be clear, cuts, are necessary in order to liberate capital, which in conjunction with a revised exemption list, can contribute towards reducing prescription costs in England. Regretfully the politicisation of the NHS has led to the word “cuts” being used as a perniciously ominous and derogatory term, demonstrating a lack of commitment to the NHS by one political party to another. The NHS may indeed be free at the point of delivery (something that should remain forever more), but in actuality the NHS is not free at all. It is funded, rather substantially, by taxpayer’s money and so it calls for responsible custodianship in the management and sensible deployment of funds within the service. In order to successfully achieve the objective of reducing prescription charges, it will require the utmost cooperation and transparency for and from all those who are working on the current prescription policy of England. Tackling the issue of continually rising prescription prices in England cannot be done on a soapbox of populism and political pandering, as this serves to the detriment of the future of the NHS and the patients.

Nnadi’s Healthcare & Pharmaceuticals is in full support of a reformed exemption list and a subsidised prescription cost through savings that arrest the continued trajectory that would see £10 plus prescription by 2025. By achieving a balance of both cuts and reformation it prevents and protects patients from the bullish, though gradually spiralling, price rises in prescription costs, as seen in cryptocurrency markets, whilst ensuring the sustainability and financial long-term welfare of the NHS and patients in England.

© All rights reserved, Nnadi’s Healthcare & Pharmaceuticals Limited, 2021.

Helpful Resources & Signposting :

If you need support with your prescription payment or health cost call;

NHS Help with Health Costs helpline: 0300 330 1343

If you are on low income and would like to see what support is available visit https://nhsbsa-live.powerappsportals.com/knowledgebase/category/?id=CAT-01286

for more information.

Prescription Charges Coalition is a group of 51 organisations calling for government to scrap prescription charges for people with long-term conditions Visit http://www.prescriptionchargescoalition.org.uk/about.html

to learn more.

References:

1

Pharmaceutical Services Negotiation Services (PSNC). Prescription charges rise to £9.35 from 1st April.< https://psnc.org.uk/our-news/prescription-charge-to-rise-to-9-35/>. Accessed 6th June 2021

2

Office for National Statistics (ONS) Unemployment rate (aged 16 and over, seasonally adjusted). <https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peoplenotinwork/unemployment/timeseries/mgsx/lms>Accessed 6th June 2021

3

Resolution Foundation. Rising unemployment is taking a huge toll on young people, even as firms are learning to live with lockdown. <https://www.resolutionfoundation.org/press-releases/rising-unemployment-is-taking-a-huge-toll-on-young-people-even-as-firms-are-learning-to-live-with-lockdown/> Accessed 6th June 2021

4

Resolution Foundation. 300,000 “forgotten unemployed” people aren’t accessing the state support to which they are entitled. <https://www.resolutionfoundation.org/press-releases/300000-forgotten-unemployed-people-arent-accessing-the-state-support-to-which-they-are-entitled/> Accessed 6th June 2021

5

Prescription Charges Coalition. Coverage of Price Rise. <http://www.prescriptionchargescoalition.org.uk/latest-news> accessed 6th June 2021

6

J Fernando. Opportunity Cost. Investopedia 2020. https://www.investopedia.com/terms/o/opportunitycost.asp accessed 12th June 2021

7

British National Formulary 75. British Medical Journal Group and Pharmaceutical Press.

8

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Costing statement: Implementing the NICE guideline on Transition between inpatient hospital settings and community or care home settings for adult with social care needs (NG27) https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng27/resources/costing-statement-2187244909 accessed 12th June 2021

9

Ibid 7

10

Buckinghamshire Healthcare NHS Trust. Management. 364FM.6 Management and treatment of cellulitis <http://www.bucksformulary.nhs.uk/docs/Guideline_364FM.pdf> accessed 12th June 2021.

11

L Steed. This is how much it costs the NHS to perform an operation to you. Surrey Live. <https://www.getsurrey.co.uk/news/surrey-news/how-much-costs-nhs-perform-14462706> accessed 12th June 2021

12

Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS). Prescription Charges: Policy Topic. < https://www.rpharms.com/recognition/all-our-campaigns/policy-a-z/prescription-charges> assessed 13th June 2021

13

The Barker Commission on the Future of Health and Social Care: A new settlement for health and social care. Final Report. <https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/field/field_publication_file/Commission%20Final%20%20interactive.pdf> assessed 13th June 2021

14

The Carter Report: Review of the Operational Productivity in NHS Providers Interim Report 2015. < https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/434202/carter-interim-report.pdf> accessed 13th June 2021

15

J Gornall. How the NHS wastes a staggering £7.6bn a year. < https://www.dailymail.co.uk/health/article-4377250/How-NHS-wastes-7-6bn-year.html> accessed 13th June 2021

16

Care Management Matters. NHS system is not financially sustainable. < https://www.caremanagementmatters.co.uk/nhs-system-is-not-financially-sustainable/> accessed 13th June 2021.

Following on from our “Faith & Medicine” article and in keeping with the theme of spirituality, I’d like to announce that the Archangel Michael stands as the patron of Nnadi’s Healthcare & Pharmaceuticals Ltd. “St Michael the Archangel, defend us in battle, be our protection against the wickedness and snares of the devil. May God rebuke him we humbly pray; and do thou, O Prince of Heavenly host, by the power of God, cast into hell Satan and all evil spirits who prowl about the world seeking the ruins of souls.” Whilst Nnadi’s Healthcare & Pharmaceuticals remains a company that will always stay true to the principles of evidence-based medicine and “Good Science”, we pledge to utilise the scientific skill, talent and ambition that this company possesses to best serve patients & customers be they in the United Kingdom or abroad. Our privilege to serve those in need of our goods & services is a commitment we do not take lightly. We are most humbled and grateful to undertake this responsibility, and thus ask for the guidance & protection of St Michael the Archangel in all our endeavours henceforth. Most Sincerely, Sonny A. Ume Founder & Managing Director

In the Western world, and specifically to Western medicine (allopathic medicine), faith commonly tends to meet medicine at the intersect of “last resort”. Sporting analogies vividly depict such dire occasions, the “Hail Mary Pass” of American Football, “The bottom of the ninth” of American baseball or “90 minutes plus stoppage time” in football (soccer). Once the game plans and tactics have been tried and exhausted to no avail, the game of the respective sports take on a more urgent, opportunistic and hopeful complexion for the teams involved. This scenario is very much reminiscent of when medicine has been deployed as the opening gambit to tackle ill health only to find it is yielding little to no dividends towards improving to the patient’s health or condition. In this situation desperate times call for desperate measures and in the face of such desperation faith is sought and clung onto. Faith and medicine enjoy a polarising duality; Spirituality versus Science, “The Unseen” versus “The Proven”, subjectivity versus objectivity, belief versus evidence. Even in the face of this presented incompatibility between Faith and Medicine, there resides a common thread that unifies both. Patients. This article will look at the importance of acknowledging faith in medicine and the role faith plays in healthcare, particularly in primary care. The opening sentiment of this article on the relationship between Faith and Medicine may appear somewhat flippant and reductive. For some patients, faith does not follow a sense of hopelessness or vulnerability. Rather faith, in their respective religion, is their North Star. Their compass in navigating their day-to-day life of which, their healthcare needs are no different. Faith is central to the identity of an individual and for the collective community and demographic. An understanding of a patient’s faith in the healthcare sector is necessary in a multicultural country like the UK and more so in her multicultural major cities such as London. According to the latest data from the ONS (Office for National Statistics) 2021 Census, Christianity remains the largest religion in London with 40.66%, with Islam, Hinduism, Judaism, Sikhism and Buddhism following in sequential order at 14.99%, 5.15%, 1.65%, 1.64% and 0.99% respectively 1. When making an eyeball comparison of the religions distribution chart from the ONS 2011 Census against the ethnic group distribution chart from the 2021 Census, it provides a quantitative and qualitative insight into where specific demographics are situated across London 2. For instance you will find a majority of the Black Afro-Caribbean demographic in South East London an area with a high number of individuals identify as Christians, Asian-Indian in West London, an area where a large majority identify as Hindus and Sikhs, Asian Pakistanis far West & East London where Islam is the dominant religion and individuals who identify as Jewish are predominantly situated in the North and North West London area. A majority people who identify within an ethnic group demographic will have some connection to a religion, which plays an integral part to shaping their culture as well as their faith. This is of significance as these individuals then to be those as risk of preventative chronic disease of which the health outcome can be a poor prognosis. The data derived from the charts below will form the basis for strategies that are to be deployed in meeting the clinical needs of the multicultural demographic in London.

Dear Reader, We’d like to apologise for our absence and inconsistency in our posting activities. We had planned for 2023 to be the year to springboard growth for the company. However, by August 2023 our plans were derailed by unapproved amendments to an investment deal, unforeseen operational changes by appointed service partner and the negligent damage to our current stock. Due this catalogues of disruptions, it resulted in the business having to concentrate its efforts on stabilizing and navigating through this thorny period. Sadly the decisive actions we took have impacted our agility and growth for 2023 heading into early 2024. It would be no stretch of the English language to deem 2023 as an annus horribilis for Nnadi’s Healthcare & Pharmaceuticals. Despite the hurdles of learning and operational obstacles to surmount, we persevere not out of foolishness or folly but out of a sense of duty and determination to contribute something positive to the country. Something positive for the nation’s economy and the health of the population too. Through Fergie’s Sparkling Water®, we have had the opportunity to connect and listen to people. We have come to gain an insight into people’s relationship with their nutrition, GP and the NHS as a whole. Through these conversations with the public, it is apparent there is still much work to do. Aside from these conversations, I would be remiss not to mention and acknowledge the kind words of support and gradual return business we have accrued in spite of all these difficulties since August 2023. We are grateful to these customers and supporters, we shall repay their faith by continuing to make strides towards securing investment. Our path towards securing investment now adopts a strategy of patience (as much as we can afford). The investment climate in the UK is constricted and conservative to nascent SME science ventures. According to an experienced business advisor, investments in the UK have dropped by 61%. Aside from the slow velocity of investment capital, there seems to be a shortage of courage and patience towards modest & sustainable business model. Investing in STEM ventures is not for the faint-hearted, but it is an investment that pays dividends both financially and socially. In this climate, we have to wait discerningly for the correct investing partner that will pull us out of the vicious cycle of traction against capital. I have full confidence in the company’s potential and mission. I hope this is a sentiment shared by our investors. We shall indeed wait and see. In the meantime, we shall continue with our daily operational activities and ambitions. We have come to accept that investment is very much now a waiting game. Kindest Regards, Sonny Ume Founder & Managing Director

Dear Reader, This year has been a year of marked progess and incremental growth in comparison to the previous year. Early into Q1, we began officially trading with Fergie’s Sparkling Water ® and have been garnering sales throughout the year. Between late Q2 and mid Q3 , we encountered challenges and hinderances in involving our marketing campaign impeding us from fully capitalising upon the double heatwave that swept through the UK in the Summer. Due to thte unwelcomed impact, we have parted ways from the responsible marketing firm that oversaw our campaign during the periods of the aforementioned quarters. New marketing partners have been identified for 2023. Despites seeing sales and an increase in social media follwers across all platforms, we have had to contend with difficult macroeconomic factors. The leading macroeconomic factor has indeed been the steep rise in inflation, exacerbated by the Russia-Ukraine conflict in March of this year leading to soaring commodity prices affecting businesses, families and individuals alike. As a result of this, the UK, amongst other countries in Europe, are enduring a cost of living crisis. In relevance to our sector, for Fergie’s Sparkling Water ® , grocery shopping (food) inflation currently stands at 14.6% (down 0.1%, 6 Dec 2022), significantly higher than this time last year’s recorded at 4.2%. To combat this inflationary environment we have decided on two courses of action. Firstly, we have opted not to engage in cost-push inflatuion from our end, which would see us pass the additional cost onto the consumer. This is clearly demonstrated by us not levying a delivery charge on the customer’s orders. Secondly, we have offered small sample packs and have revised and reduced our prices across our current SKU (flavours/lines) which now includes multiflavour packs. These practices have created new customers, returning customers and prospective customers. Regarding the later, we have seen an increase in orders left at the basket checkout (a common practice observed by e-commerce merchants and retailers). We would prefer to convert these incompleted orders to sales. We shall indeed concentrate attention and focus on this practice and these prospective customers in the coming year. Aside from opening achievements and current challenges, we have achieved milestones on a marketing and parternship front this year. In mid Q2 we were part sponsors of a well known health conference with leading dietician and nutritionist . We will explore the possibility of sponsoring this event again. In addition to this come Q1 of 2023 we will be sponsoring a University Netball Team Club for the second half of their season. We intend for this to be a promising promotional endeavour. Whilst forming sponsorship links we enagegd in our first out-of-home (OOH) marketing campaign in a thriving and bustling area within the city of London. This achievement and opportunity allowed us for to showcase our distinctive golden cans and unique and delicious flavours to passers-by in the capital. Again, we aim to incorporate this form of marketing into future marketing campaigns. Rounding up on positive fronts, the final preparations are being made towards the end of Q4 following the better articulation of our product portfolio and strategy heading into 2023. On behalf of the company I am filled with much confidence and optimism as to what lies ahead for 2023. Overall, 2022 has provided an additional 12 months that have served as an invaluable learning curve. Both in evaluation and identification and better yet, realization. And come the end of this year we realize the necessity and central importance of securing funding in 2023. I believe my confidence and optimism are not misplaced surrounding the current potential and awaiting achievements of this company. For, if we can successfully complete our next round of funding and secure sufficient capital investment, it would serve as both fuel and vehicle to propel our commercial ambitions and endeavours. Nnadi’s Healthcare & Pharmaceuticals aspires to make its contribution to the gauntlet and satellite challenges that have arisen following the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent scrutiny of the pharmaceutical industry. Given our stance towards the current perception of the pharmaceutical industry and our intended efforts to a propose remedy to the heightened scrutiny through Nnadi’s Healthcare & Pharmaceuticals’ operating model, hence there has not been a more enticing time to be involved in this sector. Nnadi’s Healthcare & Pharmaceuticals will strive to be among those enterprises, big and small, who wish to use all their efforts in tackling the challenges and seizing the opportunities that lie ahead in this field. Again, our ambition can only be realized with the necessary capital to fortify and grow based on what we have achieved so far. In closing, and returning to current matters, I would like to take this time to thank you for reading this and subsequent articles we have posted this year. I would like to thank all those who have supported and offered advice to bring us this for. And finally, above all else I would like to thank our customers who have invaluable not just in support through purchase, but in patience too. I would like to wish you and you a very Merry Christmas and a happy and prosperous New Year. May 2023 be a year of achivements and delivery for you as I hope it will be for Nnadi’s Healthcare & Pharmaceuticals. Kind Regards, Sonny Ume Founder & Managing Director Nnadi’s Healthcare & Pharmaceuticals Ltd.

Fergie’s Sparkling Water ® is delighted to announce it will be a sponsor for the second half of the University of Strathclyde Female Netball Club (USFNC). Fergie’s Sparkling Water ® can be enjoyed as part of a healthy diet, but as a thirst-quenching healthier alternative after physical activity such as sports. Increasing and encourage physical activity, through the medium of sports, is something we wish to do now and in the future. A club officer and player of the USNC, Oriana Smith said; “We have chosen Fergie's Sparkling water as one of our sponsors this year because we really believe in their product of a healthy alternative to sugary soft drinks. As a netball team who take our sport seriously, we can't wait to enjoy Fergie's drinks after our games and around Strathclyde Campus. Thanks so much Fergie's for being one of our sponsors this year!” We will certainly cheering the team on!

The pharmaceutical industry is a force for good! Our opening remark serves as a reminder and maxim within our company’s mission statement of elevating the patient’s and consumer’s perception of the pharmaceutical industry. Now more so than ever in recent times, this maxim of ours is necessary to recalibrate the perception of our industry. For failure to do so will have far reaching consequences, not just upon the pharmaceutical industry but also on public health. As it stands, Big Pharma and the remaining stakeholders within the pharmaceutical industry must, if not currently are, run through a gauntlet consisting of disenfranchised, incredulous and angry members of the public. This brief will look at the current obstacles and challenges that await Big Pharma and other industry players, whilst proffering solutions that go some way to repairing the strained relationship between pharma and the public. The objective of this reconciliation between both pharma and public seeks to restore the lack of confidence and subsequently the trust that has been broken. The future and integrity of the pharmaceutical industry depends on the mending of this relationship. Beginning with confidence itself, it is its latter crystalised end product of trust, that has been eroded or completely shattered resulting in the pharmaceutical industry being brought into disrepute. The leading contributing factor has been the lack of transparency in commercial activities and the decisions of Pfizer Inc. surrounding their vaccine. The earliest sense of opacity and perceived artifice involved the non-attendance of Albert Bourla pulling out of an initially scheduled European Parliament’s special committee on COVID (COVID committee). Mr. Bourla was not legally bound to attend nor was he subjected to any criminal punishment, as this was not an inquiry. Mr Bourla was intended to speak off the record. Mr. Bourla’s non-attendance proved irksome and did little to quell the committee’s frustration in the pursuit of answer. Another invitation has been extended to Mr Bourla. In Mr. Bourla’s place Janine Small, Pfizer’s Regional President of International Developed Markets stood in. The committee sought to address their concerns surrounding the heavily redacted vaccine purchase contract and the text messages between the Pfizer CEO and EU President Ursula von der Leyen. French MEP and COVI Committee member Veronique Trillet-Lenoir put these questions to Ms. Small. The purpose of Ms. Trillet-Lenoir’s line of questioning was to establish the relevant components about the operations in the manufacturing and delivery of the vaccines. 1 To this, Small answered that the information remains confidential for “competition reasons. This answer in the eyes of the COVI Committee ran contrary to Pfizer’s initial claim of transparency.

The role of a mother in the development of an infant is invaluable. Whether it be supporting intellectual development or social development at an early age, there remains and even more crucial form of development. Nutritional development. To mark the significance of nutritional development in the early weeks and months of a babies’ life, the first week of August (1st-7th) is considered World Breastfeeding Week by the World Alliance for Breastfeeding Action (WABA). WABA is a global network of individuals and organisations dedicated to the protection, promotion and support of breastfeeding worldwide. However, it would seem that the message and rationale promulgated by WABA faces much challenge whilst heading towards a collision course with the proprietors of instant baby formula milk (IBFM) a form of breast milk substitute (BMS) and their proliferation over the previous decades. This article will explore how and whether the marketing practices deployed to promote BMS affects and hence jeopardises breastfeeding. We shall look at the importance and significance of breastfeeding, the current challenges and barriers to breastfeeding. We’ll review the marketing practices used by brand labels of IBFM and rebuttals they propose to these claims. Finally, we shall conclude on the repercussions of these claims on the marketing practices and their impact on breastfeeding and IBFM, before providing a conclusion. Breastfeeding is one of the earliest and vital acts a mother engages in to support the physiological and nutritional development of her baby. It is for this reason why the World Health Organisation (WHO) recommends solely breastfeeding babies for the first six months of their life. 1 The WHO’s recommendation stems from the constituents of human breast milk, all of which contain basic essential nutrients such as carbohydrates, protein and fats too. Apart from breast milk being tailor made for a mother’s baby, breast milk is rich in million of live cells (white blood cells and stem cells etc.) that are immune-boosting and help organs develop and heal. Breast milk contains enzymes, growth factors, antibodies known as immunoglobulins (key in protecting the baby from illness and infections) by neutralising bacteria and viruses. In addition to this breast milk includes long-chain fatty acids, which play a pivotal part in the development of a babies nervous system, brain and eye development. Finally, breast milk contains 1,400 microRNAs which are thought to regulate gene expression crucial in preventing or halting disease development, whilst supporting the babies immune system and remodeling of the mother’s breast. 2 The development and properties of breast milk occur over three stages; colostrum, transitional milk and mature milk (foremilk & hindmilk).

Inflation, defined in simple economic terms, is when prices of goods and services generally increase (along with a rise in demand) whilst reducing the purchasing power of money as each unit of currency buys fewer goods and services. The 40th President of the United States, Ronald Reagan, once quipped, “Inflation was violent as a mugger, frightening as an armed robber and as deadly as a hit man.” And as this perpetrator is very much on the loose and as of the time of writing, poses a clear and present danger to family and households in the West. The global economy, in particularly those of the West, is emerging from the embers and effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and whilst still undergoing a jittery and steady recovery, inflation seems to have stalled and in some cases reverse growth in the West. In the United States inflation has hit an annual rate of 8.3% down from 8.5% in March, but still an inflation rate that remains close to a 40-year high.1 Across the pond, Western European nations are grappling, with inflation across the Eurozone reaching 7.5%.2 In addition to this, the raging conflict between Russia and Ukraine has exacerbated the inflationary pressures on the continent. This article will look at how inflation is impacting the UK population and the dangers towards diabetes prevention and what attainable steps or measures can be taken to tackle this. Despite the backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic, the escalation of geopolitical tension between the US, Russia and Ukraine has now regrettably broken out into military conflict as of Thursday 24th February 2022 and has sent commodity prices soaring. As of 2019, Russia and Ukraine exported more than 25% of the World’s wheat.3 Ukraine is considered the breadbasket of Europe, as 71% of Ukraine land is agricultural. Ukraine is also home to a quarter of the World’s “black soil” or “Chernozem”, which is highly fertile.

“Be yourself” , “Love who you are” and “Never apologise for being you” are common self affirmations associated with wellbeing but can extend to body positivity. The fashion, beauty and sporting industry are leading the vanguard on the encouragement of body positivity in the name of representation and diversity of body types. This is indeed a good thing and very much welcomed. However, there must be a sense of awareness and caution to the indirect promotion of any health implications, in particularly prediabetes. This article will explore the dichotomy between social norms of body positivity versus clinical (health) concerns surrounding body positivity. This article will cover, to an extent, the relationship and impact of body positivity and body image may have upon mental health, healthy weight management and how best to beat prediabetes and Type-2 diabetes. Finally, we shall cover how a healthy weight is calculated, its significance and metabolic difference between individuals. This article will not cover nor engage in any post-discussion or debate on the topic of body positivity in relation to attraction. From a medical viewpoint, attraction is a subjective, fickle and not germane to this article. Given the sensitivity of the subject it would be appropriate to cover the impact on mental health and psychological well-being. Body positivity is inextricably linked to our self-image, which is key to our sense of identity. Simply put, how we look equates to how we feel. The perpetuation and desirability in the pursuit of the “perfect body” arises primarily from various forms of consumption. Common sources and outlets of this category include; Hollywood, Reality TV, ITV’s mega-successful Love Island franchise and Meta’s Instagram, all offering a window into innocuous entertainment, whilst showcasing the latest beauty trends that go on to become the societal standard. However, this harmless form of entertainment ceases to be so when the perpetuated trends by A-listers, well-known celebrities or recognised public figures (devoid of malice or agenda on their part), are, perceived as unattainable. It is this realisation that is impactful and leaves a detrimental effect on the most vulnerable members of the public on the uses of body image- teens and adolescents. The data to support this is worrying. According to UK survey of 11-16 years olds conducted by Be Real found that 79% said how they look is important to them. Over half (52%) often worried about how they looked. 1 In a survey of young people aged 13-19, 35% said their body images cause them to ‘often’ or ‘always’ worry. Research has shown that girls are more likely to be dissatisfied with their appearance an their weight than boys.2 3 In a survey by Mental Health Foundation, 46% of girls reported that their body image caused them to worry ‘often’ or ‘always’ compared to 25% of boys.4 In addition to this UK survey by Be Real, targeted at UK adolescents, it was revealed that 36% agreed they would do whatever it took to look good with 57% saying they had considered going on a diet and 10% saying they had considered cosmetic surgery.5 Disturbingly among secondary school boys, 10% said they would consider taking steroids to achieve their goals.6 Through these surveys, young people have expressed that body image is a substantial concern. Body satisfaction and a pressure to be thin is linked to depressive symptoms such as anxiety disorders (social anxiety or panic disorder) particularly in those children who do not match societal views of the ideal body.7 8 9 Possessing a poor body image may also prevent young people from engaging in healthy behaviours, as studies have found that children with poor body image are less likely to take part in physical activity. Survey data has shown that 36% of girls and 24% of boys avoided taking part in activities like physical exercise/physical education (P.E.) due to worries about their appearance. Body image is a substantial concern identified by 16-25 year olds and is the third biggest challenge currently causing harm to young people behind a lack of employment opportunities and failure to succeed within the education system being the first two.10

To mark the Diabetes (Type-2) Prevention Week, we shall provide you with a brief overview of what prediabetes is, why it is significant, who is most at risk and what can be done to tackle it. What is prediabetes? Prediabetes, also known as non-diabetic hyperglycaemia, is a serious health condition that sees a person’s blood glucose level reside above the healthy range, but reside just below the range required for the person to be diagnosed with Type-2 Diabetes (T2D). An individual is deemed prediabetic if they have an HbA1c reading of between 42mmol/mol (6%) to 47.9mmol/mol (6.4%) or a fasting plasma glucose (FPG) of 5.5mmol/l to 6.9 mmol/l. In the UK, statistics suggest that there are 13.6 million people at risk of developing Type-2 diabetes.